PLATFORM May 2017

Getting Results from Design Thinking

Carl Turner Contributing Editor

This article was originally published in DFM’s 2017 PLATFORM series – a curated publication for leaders seeking to bring innovation into their business.

Rigorously researched and written by the DFM family, PLATFORM drew on our experience and expertise across industries, countries, and mindsets to bring you insights that you can action to drive your innovation and growth strategies.

Design Thinking — It’s a term that’s become tied to the agenda of innovation and change. It has become the ‘new black’ and migrated from the agency to the boardroom with executives recognising the need to incorporate it into their long-term strategy.

But what is design thinking? A quick google of the term will reveal a multitude of definitions and offerings—online courses and workshops teaching design thinking, agencies selling their skills to help your business, and a raft of opinions on the topic with varying degrees of substance. So where do you start? How do you sort the walk from the talk?

At Design Factory Melbourne we use many processes and models of thinking, but design thinking is the most popular go to. Yet, it’s also the least clarified. So, this month on PLATFORM we’re cutting through the noise around design thinking. Read on to discover what makes for effective design thinking.

What is Design Thinking For

Organisations today face two main challenges:

- Managing risks associated with innovation,

- Creating products, services, places to work, and communities that have meaningful emotional, social and experiential value, that drives economic value (1).

Design thinking addresses both of these challenges, head-on.

What do we mean when we talk about Design Thinking?

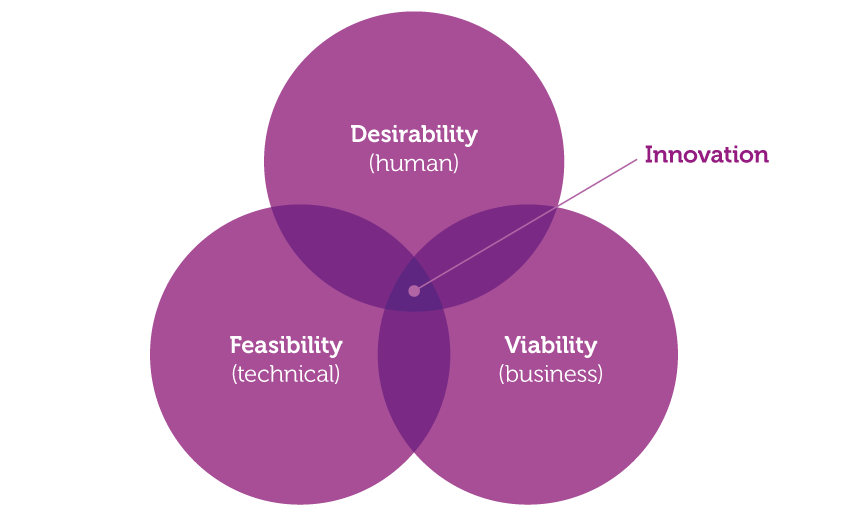

We thought about coming up with our own definition for design thinking, but we just love Tim Brown’s (2): “Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

The key takeaways from this high-level definition of design thinking are:

- Humans (such as customers and staff) ultimately decide the value of what we create. So let’s involve them in the innovation process, and aim to really understand what matters to them.

- Though it might have emerged from design disciplines, design thinking is not only for designers. And it’s not ‘owned’ by design.

- Design thinking works across silos (because that’s how the world ‘out there’ works).

- Design thinking is scalable. Use it at a team level or an organisational level.

Four Key Practical Elements of Design Thinking

So far design thinking sounds great, and we all love a venn diagram, but it’s still pretty vague. To get results from design thinking we need to get beyond the mystery.

There is ambiguity in innovating, however design thinking itself is not ambiguous.

Let’s elaborate on the four elements we believe are at the core of getting results from design thinking:

1. Involve Customers/Staff in the Innovation Process, Early and Often

It’s surprising how often companies focus on internal efficiencies and business priorities… and forget to consider the impact on the customer or their staff. Design thinking emphasises creating innovation that is desirable for humans (customers and staff).

Humans (such as customers and staff) ultimately decide the value of what we create.

For example:

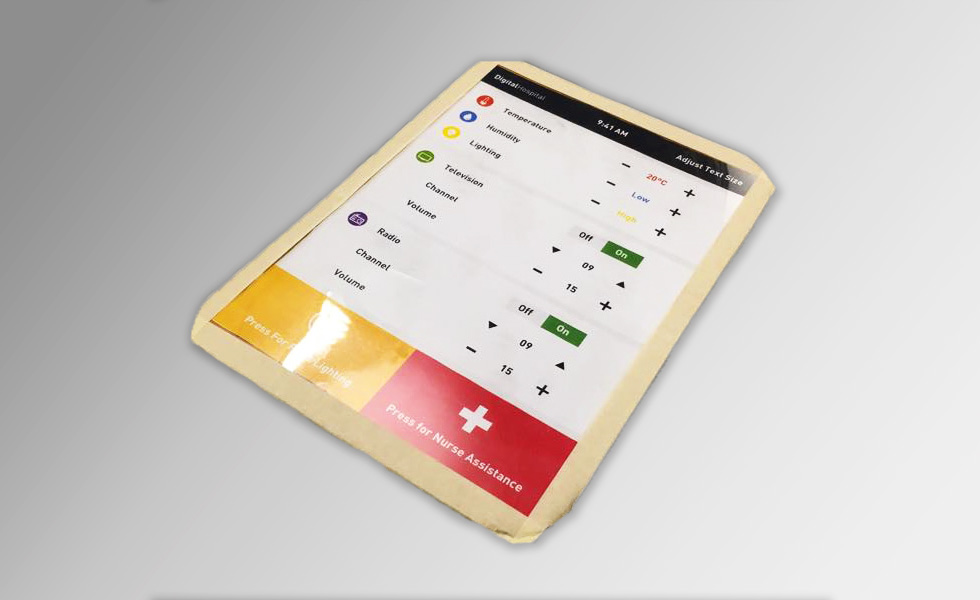

A DFM team used rough cardboard prototypes to help them speak with nurses about what it’s like working in a trauma emergency situation. The prototypes helped reveal assumptions the team had about how nurses need to access information whilst treating a trauma patient. This early involvement of nurses shifted the direction of the project away from relying solely on wearable devices.

A DFM team gained important insight into a problem by showing rough cardboard prototypes to nurses (2014).

Takeways:

- Bring customers and staff together to share perspectives and build empathy.

- Help customers (who may include staff) contribute to early, mid and later stages of the process. Doing so facilitates transfer of tacit knowledge, will reduce risk of developing the wrong thing, and increases likelihood of creating value for customers and the business.

2. Use Methods, Not Just Tools

Design thinking tools are a dime a dozen. Empathy maps, journey maps, rapid prototyping, How might we…? questions… The list goes on, and everyone’s got a stash of them. Many of these tools can be used for different purposes, at different stages of the innovation process. Great design thinking results come from using these tools effectively, to propel us through the innovation process.

Imagine you’re hammering a nail into the wall. If you’re skilled you’ll hit the nail in straight with two or three hits. If you’re an occasional DIY’er you’re more likely to bend the nail, and have to start again. Or worse still, miss it entirely and damage the wall or your thumb! The hammer is the tool. The method is how you swing the hammer. A method is more than a tool.

The difference between swimming or sinking in the ambiguity of innovation is largely about the methods we use.

A method is more than a tool.

For example:

Methods may involve research design, participant selection, equipment and materials selection, researcher roles and actions taken by participants, as well as considerations for ethical research. There is considerable skill in pulling all this together in a way that supports the innovation process and is relevant for the project.

A DFM team tasked with improving the library experience used paper planes and puzzle pieces to gather feedback from users. Unlike a traditional survey their method made interaction nostalgic and second nature, resulting in high engagement and quality data. (2015)

Takeaways:

- Invest in expert knowledge of methods and skills in applying methods.

- Sequence methods to support and drive the process.

- Engage research participants in ethical ways.

3. Growth Mindset

Innovation is generally presented as sexy, cool, fun. The truth is, innovation is hard work! It requires the confidence and ability to embrace the “potential for unexpected learning…and great progress” (3). This requires a growth mindset (as opposed to a fixed mindset) (4), which Design Factory Melbourne works to foster through its Principles and activities.

What does a growth mindset look like? It can include empathising with other perspectives; adopting a ‘beginner’s mind’, managing ambiguity; imagining; exploring new possibilities; seeking diversity of thought, and persevering.

The truth is, innovation is hard work!

For example:

DFM integrates mindset-building into the innovation process and physical space. This may involve anything from making A Desert Called Innovation together in the DFM kitchen, to a formal facilitated feedback session (‘I like, I wish’).

DFM students creating pizzas that represent their team mates. The activity encourages empathy, imagination and fun! (March 2015)

Takeaways:

- Build personal and team development into the process. Facilitate activities that develop cross-disciplinary communication skills, creative confidence and a culture of safety. Read more about this in our previous article, More than Innovations.

- Put team values on the wall and encourage people to share what they mean to them.

- Find creative ways, within organisational constraints, of using space, materials, prototyping quickly with customers/staff.

4. An Innovation Process

An innovation process is what puts design thinking to work (5). It is a structured framework for doing design thinking. A clear process provides direction, timeframes and goals for getting results from design thinking.

Innovation processes come in many forms. A good process is tailored to the type of project. Common to processes that activate design thinking are iterative stages of divergence (exploring options) and convergence (making decisions). It’s through these stages that design thinking propels us from ambiguity to clarity.

An innovation process is a structured framework for doing design thinking

For example:

The diagram below visualises the innovation process of a DFM project (2015).

Credit to D Newman for the ‘squiggle’! (6)

Takeaways:

- Create an innovation process that’s fit for the nature of problem, available time and goals.

- Plan to learn about the problem and people involved, before entering ‘solution mode’.

- Use ‘lo-fi’ prototyping methods early and often, to explore multiple options, to learn and to make decisions.

Remember:

Design Thinking = Mindset + Methods + Creating value for humans and business

AND

Design Thinking + Innovation Process = Innovation Capability = Results

Join us for one of our monthly breakfasts where you can meet others on a similar journey, or talk to us about a project. Through partnering with DFM we offer an opportunity to participate, to experience design thinking with us, to see first hand how we apply methods in the innovation process, and the outcomes of those methods.

References

1. Howkins J 2009, Creative Ecologies: where thinking is a proper job, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane

2. Ideo 2017, Design Thinking, http://www.ideou.com/pages/design-thinking

3. Wenger-Trayner E, & Wenger-Trayner B 2014. Learning in a landscape of practice: A framework. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton-O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, & B. Wenger-Trayner (Eds.), Learning in landscapes of practice : Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning (pp. 13-29): Taylor and Francis. p.17

4. Dweck C 2016, ‘What Having a Growth Mindset Actually Means’, Harvard Business Review, 13 January 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-a-growth-mindset-actually-means

5. Ideo n.d., Design Thinking for Educators, https://designthinkingforeducators.com/design-thinking/

6. Newman D, The Squiggle of Design, http://cargocollective.com/central/The-Design-Squiggle